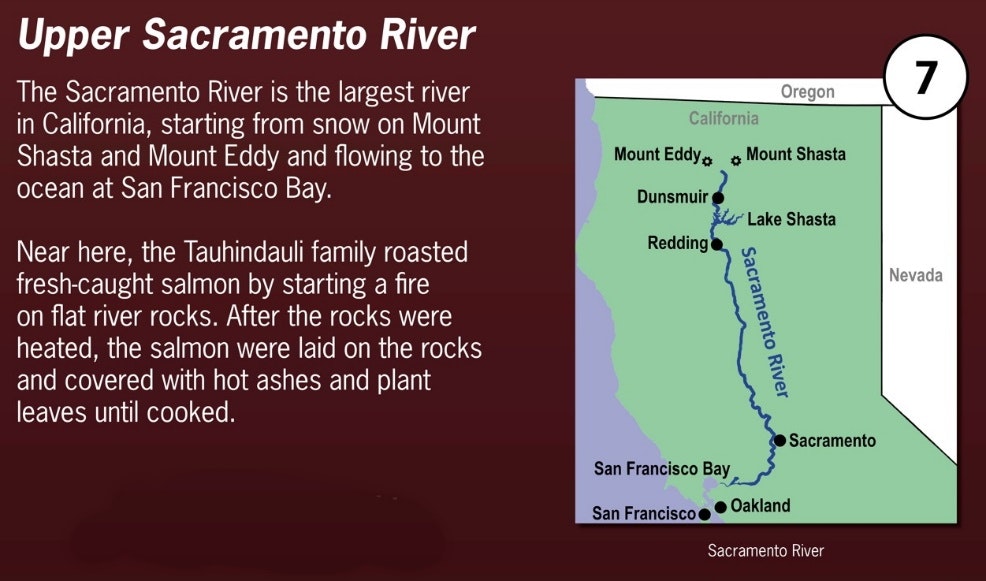

Self-Guided Tour Sign #7 - Upper Sacramento River

From its traditional headwater springs in Mount Shasta City Park, the Sacramento River flows south for 400 miles before reaching the Sacramento–San Joaquin River Delta and San Francisco Bay. The “Upper Sac” as it’s sometimes called, is prized around the world for its natural beauty, and recreational and fishing opportunities.

Before the construction of Shasta Dam, large amounts of salmon annually returned from the Pacific Ocean to the Upper Sacramento to spawn, providing Indigenous peoples an important source of food. These early people developed specialized methods of catching the fish, and preparing and storing their catch. If not eaten soon after being caught, salmon meat could be dried and preserved as a powder to mix with acorn meal and other foods during the long winter months. The river also provided plants that the Indigenous people ate or used for medicine.

For more detailed information, continue reading below.

Although traditionally the headwaters of the Sacramento River are placed in Mount Shasta City Park, there are a number of creeks and springs which all contribute to the river in its farthest northern reaches, including Castle Creek coming down from Castle Lake. All of these northern sources drain into Lake Siskiyou, about 10 miles north of Tauhindauli Park. From Lake Siskiyou, the river begins by flowing through scenic Box Canyon, with sheer vertical walls of lava thirty-to-fifty-feet high lining the river on both sides. Below Box Canyon, the river begins its descent through the steep winding folds of the Sacramento River Canyon—dense forests on both sides of the river cover the canyon walls. Along the way, about three miles north of Tauhindauli Park, the waters of Mossbrae Falls drop dramatically from a fern- and moss-covered cliff face directly into the river.

South of Tauhindauli Park, the river continues its passage through the Sacramento River Canyon—a canyon that the river itself created during the most recent 450,000 years. Many creeks and streams feed into the river during this part of its journey, including Salt Creek, the southern boundary of the Okwanuchu tribe.

When the river reaches Lake Shasta, about 40 miles south of Tauhindauli Park, it is joined by its two main northernmost tributaries, the McCloud River and the Pit River. The McCloud River also has its sources in the foothills of Mount Shasta, while in wet years the Pit River starts in Goose Lake, which straddles the California-Oregon border.

All told, the river drains about 26,500 square miles in 19 California counties, including California’s fertile Central Valley. The Sacramento and its wide natural floodplain were once abundant in fish and other aquatic creatures, notably one of the southernmost large runs of chinook salmon in North America. For perhaps the most recent 8,000-10,000 years, humans have depended on the vast natural resources of the watershed, which had one of the densest Native American populations in North America. The river has provided a route for trade and travel since ancient times. Hundreds of tribes sharing regional customs and traditions inhabited the Sacramento Valley, first coming into contact with European explorers in the late 1700’s. The Spanish explorer Gabriel Moraga named the river “Rio de los Sacramentos” in 1808, later shortened and anglicized into “Sacramento”.

In the 19th century, gold was discovered on the American River, a tributary of the Sacramento River, starting the California Gold Rush and an enormous population influx to the state. Overland trails such as the California Trail and Siskiyou Trail guided hundreds of thousands of people to the gold fields. By the late part of the 1860’s many of the new immigrants turned to farming and ranching. Many populous communities were established along the Sacramento River, including the state capital of Sacramento. Intensive agriculture and mining contributed to pollution in the Sacramento River, and to significant changes in the river's environment.

Since the 1930’s, the watershed has been intensely developed for water supply and generating of hydroelectric power. Today, large dams impound the river and almost all of its major tributaries. The Sacramento River is used heavily for irrigation and serves much of Central and Southern California through the canals of giant state and federal water projects. While it's now providing water to over half of California's population and supporting the most productive agricultural area in the nation, these changes have left the Sacramento greatly modified from its natural state and have caused the decline of its once-abundant fisheries.