Self-Guided Tour Sign #9 - Trail to City Park and Botanical Gardens

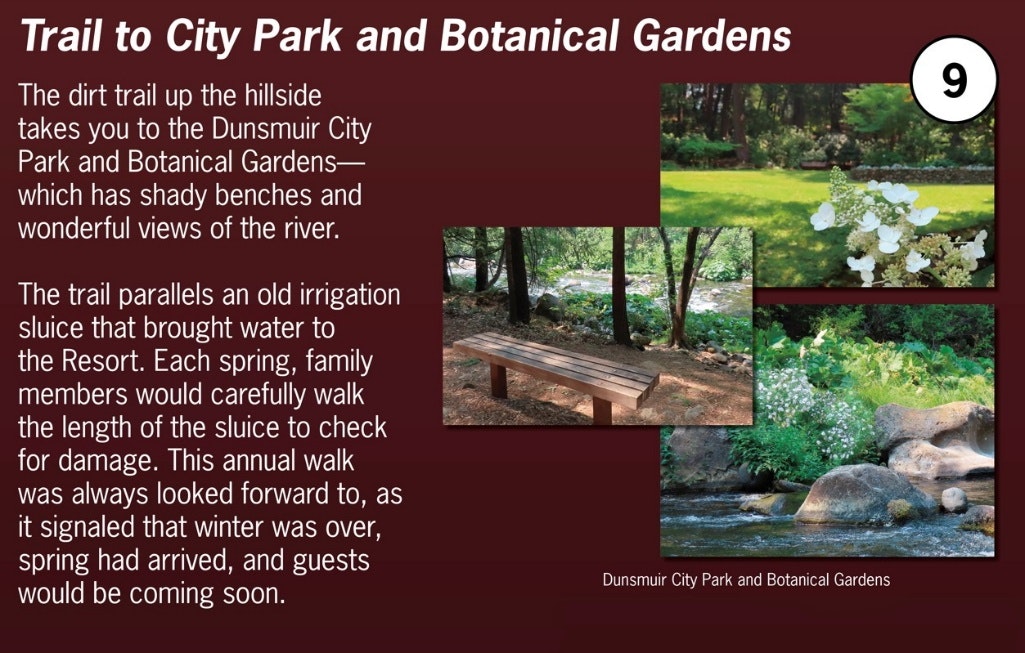

Dunsmuir’s City Park and Botanical Gardens are a well-maintained oasis open to the public along the Sacramento River. Lawns, gardens, picnic tables, benches, restrooms, and a children’s playground all await the visitor. A particular source of pride are well-tended botanical gardens, overseen by members of the Dunsmuir Garden Club. These gardens are filled with beautiful native plants and species varieties of familiar garden plants. Walking the trail to the Park and Botanical Gardens will take about 15 minutes each way. The trail from here to the City Park parallels an old irrigation sluice built in the mid-1800’s to bring water to the Upper Soda Springs Resort and its guests. Today almost nothing remains of the old irrigation sluice as the last traces of it were washed away in a 1991 Sacramento River flood.

For more detailed information, continue reading below.

The original Gold Rush-era claim owned by Ross and Mary McCloud extended north along the banks of the Sacramento River well into today’s north Dunsmuir. With the arrival of the surveying crews before the arrival of the railroad in the mid-1880’s, the family agreed to transition their claim to a standardized square-shaped property outline. Similarly, with the formation of the City of Dunsmuir in the late 1880’s, the property making up today’s Dunsmuir Ballpark, Community Center, and City Park and Botanical Gardens was transferred to the City of Dunsmuir for public use.

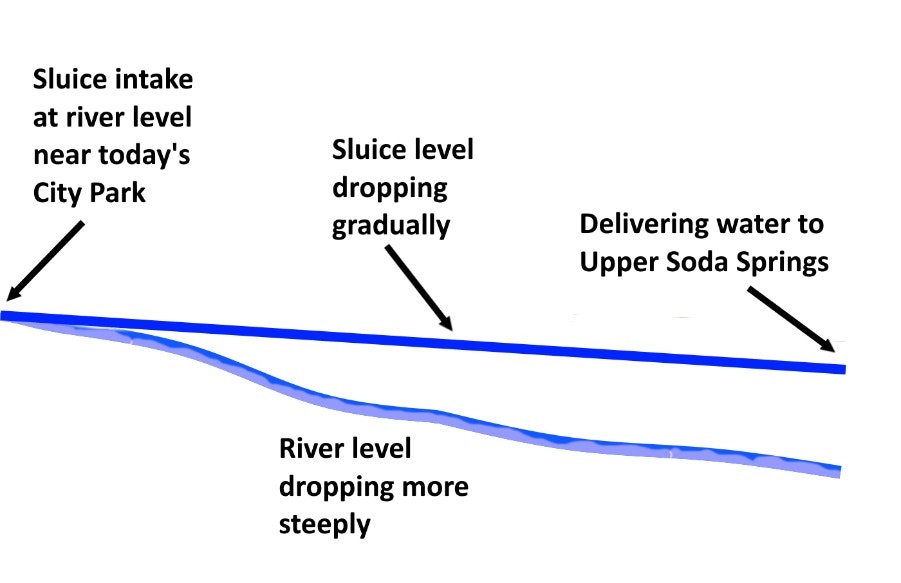

Water for Upper Soda Springs’ guests, crops, and animals was first carried bucket-by-bucket from the Sacramento River to the buildings here. However, by the 1860’s and 1870’s an easier and more reliable method of providing water to Upper Soda Springs was created—a water sluice was constructed to bring water from the river. That sluice brought water from the Sacramento to where you are standing now.

To make the sluice, first the base of the hillside along the riverbank north of here was made into a wide, level pathway, starting here and ending near today’s Dunsmuir City Park, about one-quarter mile north of here. The water sluice was built into this pathway. The sluice then took in river water at the north (upriver) end, and delivered the water by gravity flow down to the buildings, crops, and animals here.

Intake of water at the upper end was controlled by a series of gates in the sluice that could be raised or lowered to allow in more or less river water. The water then traveled by gravity in the sluice parallel to the river until it reached Upper Soda Springs. There the water entered another series of gates that controlled where on the grounds the water would be directed. Some of the water would be used in the kitchen and dining room, some could be directed to the stables, and still more of the water could be directed for watering the gardens and crops.

The sluice and gates were subject to damage in the winter and early spring if the Sacramento River rose to high water levels and washed away the intake gates or the riverbank supporting the sluice itself. Sometimes also winter storms would bring down trees, underbrush, or dirt and rocks from the hillside into the sluice, blocking the passage of the water.

In mid-spring, after the risk of flood and storm damage had passed, members of the family and employees would walk the length of the sluice checking for damage—this walk “to the head of the ditch” (as the sluice was affectionately called) became an annual ritual, as the Resort was preparing for the arrival of that year’s new summer guests.

Even after the Upper Soda Springs Resort closed in the early 1920’s, members of the McCloud-Masson family maintained the sluice to irrigate the substantial gardens and orchard that remained on the property. The sluice was used as a source of water into the 1960’s by family members.

By the 1970’s the sluice was no longer used as a water source, and it began to fall into disrepair. However, the level pathway where the sluice had been remained a favorite walking path for fisherfolk and knowledgeable locals. Unfortunately, very high Sacramento River flood waters in 1991 washed away much of the riverbank supporting the pathway, and washed away the sluice channel itself—which had been there for over 100 years. Now, almost nothing remains of the old sluice, and only old-timers know where to look for the last remaining evidence of it.