Self-Guided Tour Sign #8 – Stables and Cowsheds

Everyday life in the 1850’s in Northern California often centered around horses and to a lesser extent, mules. Horses were used to transport goods and people, both for individuals and pulling stagecoaches and cargo wagons. Mules were used to carry bulk items, like food and manufactured goods, to people in Northern California. The stables here at Upper Soda Springs were an important part of the network of stables for these essential animals. In addition, the Resort kept cattle and chickens to provide food for the Resort guests. These farm animals produced eggs, cheese, fresh milk, and butter, in addition to meat for the dinner table.

For more detailed information, continue reading below.

Horses and mules required a high level of care and protection, and a network of reliable, well-stocked, safe stables was critical. Upper Soda Springs became a central point in that network. In the late 1850’s, Ross McCloud was elected to the position of County Surveyor for Siskiyou County, a very important position in those pioneer days. Perhaps his most important job was to plan and survey the construction of a reliable stagecoach road heading south from Yreka connecting to the rest of California.

Up until that time, there were only footpaths and rough trails leading from Yreka to the Sacramento River Canyon. Footpaths were usable by travelers on foot and horseback, and mule trains could use commercial trails (which were an improvement over footpaths)—but neither could be used by stagecoaches. Stagecoaches were essential in the 1850’s. Stagecoaches could carry groups of travelers longer distances in greater safety and comfort, and there were many travelers for whom a stagecoach was the only option.

However, stagecoaches could not use the existing footpaths and rough trails which wound and twisted their way through the forests and range lands south of Yreka. Instead, stagecoaches needed a specially constructed roadway with bridges and culverts, wide enough for a stagecoach and made relatively level and smooth. A stagecoach road needed to be carefully surveyed and planned, with dedicated work crews clearing forest land, leveling or filling steeper areas, and building bridges and culverts.

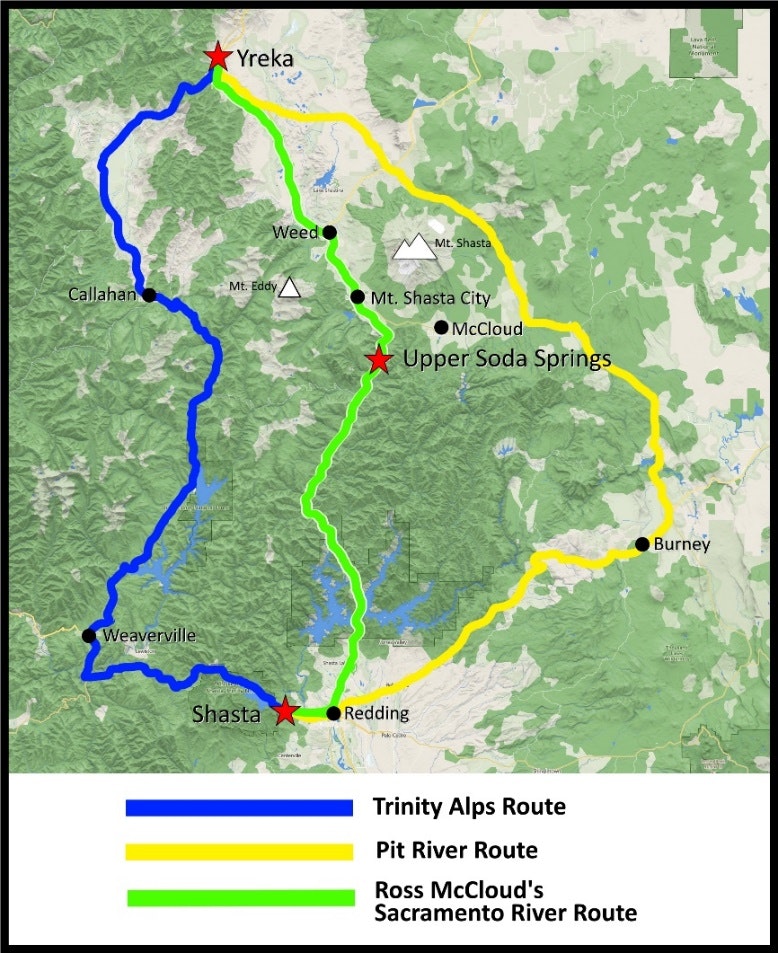

Ross had to decide among three competing options for this stagecoach road from Yreka—a potential stagecoach road to the west through the Trinity Alps, a potential road to the east along the Pit River, and a central option along the Sacramento River Canyon.

Each route had its pluses and minuses. The western Trinity route would be somewhat easier to construct, but it would be impassable during cold and snowy months. The eastern Pit River route would also be easier to build, but was much longer and passed through dangerous territory. The central route through the Sacramento River Canyon was the shortest route, would be open all year, and passed through no dangerous territory—however, the Sacramento River Canyon was much steeper and more twisty than the other two routes.

Ross used his surveyor’s skills and good judgment to conclude that the Sacramento River Canyon route would be the best option for the road south from Yreka into the rest of California. Ross’s decision was later validated, by the way, by the railroads, which came to the same conclusion in the late 1800’s, and by the railroad and highway builders of the twentieth century. The Union Pacific Railroad and Interstate-5 today follow the same Sacramento River Canyon route, which Ross had initially envisioned and selected.

Ross surveyed the route of the first reliable stagecoach road south from Yreka—which led directly to Upper Soda Springs. Ross’s original stagecoach road can still be driven in your car, heading north from where you are today all the way to Yreka, and it still is known as “Stagecoach Road” today—today’s name (with several variations) discloses its origin as the actual original stagecoach road to Yreka.

Stagecoach travelers coming south from Oregon and Washington would stop overnight at Yreka, some 45 miles to the north. Then leaving Yreka, and heading south, after the end of long day, they would arrive at Upper Soda Springs to spend the night here. As importantly, the stagecoach horses were taken out of their harnesses here, and then cared for, well-fed and rested overnight in the stables here. The following morning, the travelers would continue south on horseback, while the stagecoach would return north with a fresh team of horses.

Travelers spending the night here at Upper Soda Springs would expect dinner in the evening, breakfast in the morning, and lunch at midday if they were spending several days here. The inn was the only settlement for miles around. There was no town of Dunsmuir yet (Dunsmuir would not come into existence for another 30 years until the arrival of the railroad in the late 1880’s). Instead, cows and other farm animals were an important source of food for the guests at the inn. The stables, cowsheds and chicken coops for Upper Soda Springs were located in front of where you are standing now.